In this tutorial you will find some of the best C IDEs with compiler for Windows Vista, XP, 7, 8, 8.1, 10, Linux, and Mac OS X, that will help you to write your C program (programname.c) and as well as compile the program in the same environment. Download Mac software in the Compilers category. Convert Python scripts into executable Mac OS X applications. Mar 28th 2015, 07:41 GMT. Mac OS X 10.3 or later. Install gcc; 1,713 downloads; 285.95 MB; OSX GCC Installer 0.3. Installs GCC on your Mac. Mar 24th 2015, 12:14 GMT.

You have finally made the move to become a programmer. You've registered for a course, you have your texts and manuals, and you've fired up your trusty Mac. This is exciting! You think you are all set, and then it hits: they want you to have a compiler. What the heck is that? We'll explain this and help you to get a C compiler for Mac up and running on your computer. If you are relatively new to the Mac, you can develop your skills with a course on getting started with a Mac.

The compiler is the last step in turning your code into a program that runs on your computer. Mind map for pc and mac. You learn the C language to write source code. Source code cannot be understood and run by a computer in this state. It has to be converted to code that the computer can run. This is the job of the compiler. You feed your source code in to the compiler and it will either give you an executable program or a long list of error codes telling you why it couldn't make the program. Source code can be written on any platform. It is meant for humans and is the same on any operating system. The compiler, on the other hand, has to be specific for the operating system where the program will run.

Compilers usually produce code that will run faster than the alternative, interpreters. The executable program can be distributed without the source code, which makes it harder for anyone to steal the programming ideas that went into the program. A disadvantage of compilers is that the compiling step adds time to the development process because the whole program must be compiled each time a change is made.

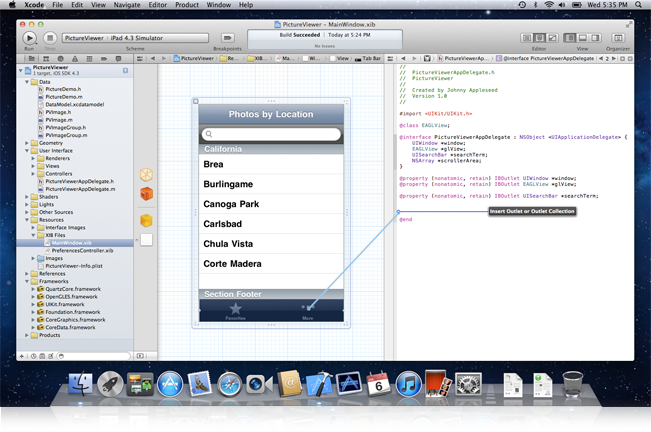

C Compiler for Mac using Xcode

The most recommended way to get a C compiler for your Mac is to use Xcode. This uses gcc, the popular open source C compiler. The details vary for each version of OS X. We'll go through the recent versions here. You will have to register as an apple developer to get access to these tools. In order to do these installs, you will be using Terminal to work at the command line. Get a solid foundation on the Mac command line with this course.

For all of the versions of OS X, you will be downloading Xcode. Xcode is an Integrated Development Environment, or IDE. An IDE allows you to write, compile, and debug a program from one central interface. Xcode can act as an IDE for C programming. All of the install methods involve first getting Xcode, then making the gcc compiler available outside of Xcode, and then installing a newer version of gcc.

For OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard, download Xcode 3 from the Apple Developer Site. This will give you a working version of gcc, but it is an older version. If you want or need a more up to date version, that is available at High Performance Computing for Mac OS X. You can install this after installing Xcode. The files must be unzipped and installed at the command line. After that, you will need to update your Shell resource file so that the newer versions are used. Details can be found at Installing the GNU compilers on Mac OS X.

For OS X 10.7 Lion, you must get Xcode 4 from the Mac App Store. It is free, but you need to supply credit card information in order to have an App Store account. For Xcode 4.2, what you download from the App Store is an installer, which you then run. For Xcode 4.3, it is installed automatically, but it does not have gcc in the correct location. To finish the job, start Xcode and go to Preferences, Downloads, Components. Click on the Install button that is next to Command Line Tools. This gives you older versions of gcc. For the newest versions, you can use High Performance Computing for Mac OS X, as described for OS X 10.6. The process is similar and details can also be found at Installing the GNU compilers on Mac OS X.

OS X 10.8 will be very similar to 10.7. Install Xcode, then install the command line tools from the preferences. You can then get the newer versions of gcc as described for version 10.7.

OS X 10.9 Mavericks will use Xcode 5 and a revised process. Xcode 5 does not have the option to install the command line version of gcc. Instead, ensure that Xcode 5 has all available updates installed by checking from within the program. Then go to the Apple Developer Site and find the latest version of Command Line Tools (OS X Mavericks) for Xcode. It is a standard installer package. Finally, you can update the version of gcc in a manner similar to the other versions of OS X.

Other C compilers for Mac

Apple has extended the gcc compiler with a version called llvm. It incorporates more modern functioning and has a different licensing model needed by Apple for its proprietary software. Clang is an IDE for this compiler. It is designed to give more user-friendly error messages. Clang will give you the latest tools used by Apple for development. The downside is that there is no installer. It has to be built from source code, which means that you will need gcc already. Details are given at the llvm site.

Another option is given by Eclipse. Eclipse is a popular IDE for Java. The CDT plugin for Eclipse gives it the ability to compile C programs and become an IDE for C. Details can be found at the CDT page of the Eclipse site.

Now that you have a C compiler for your Mac, you can try a tutorial to write a simple program. Then get a solid start in C programming with this course for beginners. If you already know one language, extend your skills with a course for intermediate coders.

Background:

In versions of Mac OS up to version 9, the standard representation for text files used an ASCII CR (carriage return) character, value decimal 13, to mark the end of a line.

Mac OS 10, unlike earlier releases, is UNIX-like, and uses the ASCII LF (line feed) character, value decimal 10, to mark the end of a line.

Best programming language for mac. The question is, what are the values of the character constants 'n' and 'r' in C and C++ compilers for Mac OS releases prior to OS X?

There are (at least) two possible approaches that could have been taken:

- Treat

'n'as the ASCII LF character, and convert it to and from CR on output to and input from text streams (similar to the conversion between LF and CR-LF on Windows systems); or - Treat

'n'as the ASCII CR character, which requires no conversion on input or output.

There would be some potential problems with the second approach. One is that code that assumes 'n' is LF could fail. (Such code is inherently non-portable anyway.) The other is that there still needs to be a distinct value for 'r', and on an ASCII-based system CR is the only sensible value. And the C standard doesn't permit 'n' 'r' (thanks to mafso for finding the citation, 5.2.2 paragraph 3), so some other value would have to be used for 'r'.

What is the output of this C program when compiled and executed under Mac OS N, for N less than 10?

The question applies to both C and C++. I presume the answer would be the same for both.

The answer could also vary from one C compiler to another — but I would hope that compiler implementers would have maintained consistency with each other.

To be clear, I am not asking what representation old releases of Mac OS used to represent end-of-line in text files. My question is specifically and only about the values of the constants 'n' and 'r' in C or C++ source code. I'm aware that printing 'n' (whatever its value is) to a text stream causes it to be converted to the system's end-of-line representation (in this case, ASCII CR); that behavior is required by the C standard.

The values of the character constants r and n was the exact same in Classic Mac OS environments as it was everywhere else: r was CR was ASCII 13 (0x0d); n was LF was ASCII 10 (0x0a). The only thing that was different on Classic Mac OS was that r was used as the 'standard' line ending in text editors, just like n is used on UNIX systems, or rn on DOS and Windows systems.

Here's a screenshot of a simple test program running in Metrowerks CodeWarrior on Mac OS 9, for instance:

Keep in mind that Classic Mac OS systems didn't have a system-wide standard C library! Functions like printf() were only present as part of compiler-specific libraries like SIOUX for CodeWarrior, which implemented C standard I/O by writing output to a window with a text field in it. As such, some implementations of standard file I/O may have performed some automatic translation between r and n, which may be what you're thinking of. (Many Windows systems do similar things for rn if you don't pass the 'b' flag to fopen(), for instance.) There was certainly nothing like that in the Mac OS Toolbox, though.

I've done a search and found this page with an old discussion where especially the following can be found:

The Metrowerks MacOS implementation goes a step further by

reversing the significance of CR and LF with regard to

the ‘r' and ‘n' escapes in i/o involving a file, but not

in any other context. This means that if you open a FILE or

fstream in text mode, every ‘r' will be output there as

an LF as well as every ‘n' being output as CR, and the same

is true of input – the escape-to-ASCII-binary correspondences

are reversed. They are not reversed however in memory, e.g.

with sprintf() to a buffer or with a std::stringstream.

I find this confusing and, if not non-standard, at least

worse than other implementations.

It turns out there is a workaround with MSL – if you open

the file in binary mode then ‘n' always LF and

‘r' always CR. This is what I wanted but in getting

this information I also got a lot of justification from

folks over there that this was the 'standard' way to get

what I wanted, when I feel like this is more like a workaround

for a bug in their implementation. After all, CR and LF

are 7-bit ASCII values and I'd expect to be able to use

them in a standard way with a file opened in text mode.

(An answer makes clear that this is indeed not a violation of the standard.)

So obviously there was at least one implementation which used n and r with the usual ASCII values, but translated them in (non-binary) file output (by just exchanging them).

C-language specification:

5.2.2

…

2 Alphabetic escape sequences representing nongraphic characters in the execution character set are intended to produce actions on display devices as follows:

…

n (new line) Moves the active position to the initial position of the next line.

r (carriage return) Moves the active position to the initial position of the current line.

For all of the versions of OS X, you will be downloading Xcode. Xcode is an Integrated Development Environment, or IDE. An IDE allows you to write, compile, and debug a program from one central interface. Xcode can act as an IDE for C programming. All of the install methods involve first getting Xcode, then making the gcc compiler available outside of Xcode, and then installing a newer version of gcc.

For OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard, download Xcode 3 from the Apple Developer Site. This will give you a working version of gcc, but it is an older version. If you want or need a more up to date version, that is available at High Performance Computing for Mac OS X. You can install this after installing Xcode. The files must be unzipped and installed at the command line. After that, you will need to update your Shell resource file so that the newer versions are used. Details can be found at Installing the GNU compilers on Mac OS X.

For OS X 10.7 Lion, you must get Xcode 4 from the Mac App Store. It is free, but you need to supply credit card information in order to have an App Store account. For Xcode 4.2, what you download from the App Store is an installer, which you then run. For Xcode 4.3, it is installed automatically, but it does not have gcc in the correct location. To finish the job, start Xcode and go to Preferences, Downloads, Components. Click on the Install button that is next to Command Line Tools. This gives you older versions of gcc. For the newest versions, you can use High Performance Computing for Mac OS X, as described for OS X 10.6. The process is similar and details can also be found at Installing the GNU compilers on Mac OS X.

OS X 10.8 will be very similar to 10.7. Install Xcode, then install the command line tools from the preferences. You can then get the newer versions of gcc as described for version 10.7.

OS X 10.9 Mavericks will use Xcode 5 and a revised process. Xcode 5 does not have the option to install the command line version of gcc. Instead, ensure that Xcode 5 has all available updates installed by checking from within the program. Then go to the Apple Developer Site and find the latest version of Command Line Tools (OS X Mavericks) for Xcode. It is a standard installer package. Finally, you can update the version of gcc in a manner similar to the other versions of OS X.

Other C compilers for Mac

Apple has extended the gcc compiler with a version called llvm. It incorporates more modern functioning and has a different licensing model needed by Apple for its proprietary software. Clang is an IDE for this compiler. It is designed to give more user-friendly error messages. Clang will give you the latest tools used by Apple for development. The downside is that there is no installer. It has to be built from source code, which means that you will need gcc already. Details are given at the llvm site.

Another option is given by Eclipse. Eclipse is a popular IDE for Java. The CDT plugin for Eclipse gives it the ability to compile C programs and become an IDE for C. Details can be found at the CDT page of the Eclipse site.

Now that you have a C compiler for your Mac, you can try a tutorial to write a simple program. Then get a solid start in C programming with this course for beginners. If you already know one language, extend your skills with a course for intermediate coders.

Background:

In versions of Mac OS up to version 9, the standard representation for text files used an ASCII CR (carriage return) character, value decimal 13, to mark the end of a line.

Mac OS 10, unlike earlier releases, is UNIX-like, and uses the ASCII LF (line feed) character, value decimal 10, to mark the end of a line.

Best programming language for mac. The question is, what are the values of the character constants 'n' and 'r' in C and C++ compilers for Mac OS releases prior to OS X?

There are (at least) two possible approaches that could have been taken:

- Treat

'n'as the ASCII LF character, and convert it to and from CR on output to and input from text streams (similar to the conversion between LF and CR-LF on Windows systems); or - Treat

'n'as the ASCII CR character, which requires no conversion on input or output.

There would be some potential problems with the second approach. One is that code that assumes 'n' is LF could fail. (Such code is inherently non-portable anyway.) The other is that there still needs to be a distinct value for 'r', and on an ASCII-based system CR is the only sensible value. And the C standard doesn't permit 'n' 'r' (thanks to mafso for finding the citation, 5.2.2 paragraph 3), so some other value would have to be used for 'r'.

What is the output of this C program when compiled and executed under Mac OS N, for N less than 10?

The question applies to both C and C++. I presume the answer would be the same for both.

The answer could also vary from one C compiler to another — but I would hope that compiler implementers would have maintained consistency with each other.

To be clear, I am not asking what representation old releases of Mac OS used to represent end-of-line in text files. My question is specifically and only about the values of the constants 'n' and 'r' in C or C++ source code. I'm aware that printing 'n' (whatever its value is) to a text stream causes it to be converted to the system's end-of-line representation (in this case, ASCII CR); that behavior is required by the C standard.

The values of the character constants r and n was the exact same in Classic Mac OS environments as it was everywhere else: r was CR was ASCII 13 (0x0d); n was LF was ASCII 10 (0x0a). The only thing that was different on Classic Mac OS was that r was used as the 'standard' line ending in text editors, just like n is used on UNIX systems, or rn on DOS and Windows systems.

Here's a screenshot of a simple test program running in Metrowerks CodeWarrior on Mac OS 9, for instance:

Keep in mind that Classic Mac OS systems didn't have a system-wide standard C library! Functions like printf() were only present as part of compiler-specific libraries like SIOUX for CodeWarrior, which implemented C standard I/O by writing output to a window with a text field in it. As such, some implementations of standard file I/O may have performed some automatic translation between r and n, which may be what you're thinking of. (Many Windows systems do similar things for rn if you don't pass the 'b' flag to fopen(), for instance.) There was certainly nothing like that in the Mac OS Toolbox, though.

I've done a search and found this page with an old discussion where especially the following can be found:

The Metrowerks MacOS implementation goes a step further by

reversing the significance of CR and LF with regard to

the ‘r' and ‘n' escapes in i/o involving a file, but not

in any other context. This means that if you open a FILE or

fstream in text mode, every ‘r' will be output there as

an LF as well as every ‘n' being output as CR, and the same

is true of input – the escape-to-ASCII-binary correspondences

are reversed. They are not reversed however in memory, e.g.

with sprintf() to a buffer or with a std::stringstream.

I find this confusing and, if not non-standard, at least

worse than other implementations.

It turns out there is a workaround with MSL – if you open

the file in binary mode then ‘n' always LF and

‘r' always CR. This is what I wanted but in getting

this information I also got a lot of justification from

folks over there that this was the 'standard' way to get

what I wanted, when I feel like this is more like a workaround

for a bug in their implementation. After all, CR and LF

are 7-bit ASCII values and I'd expect to be able to use

them in a standard way with a file opened in text mode.

(An answer makes clear that this is indeed not a violation of the standard.)

So obviously there was at least one implementation which used n and r with the usual ASCII values, but translated them in (non-binary) file output (by just exchanging them).

C-language specification:

5.2.2

…

2 Alphabetic escape sequences representing nongraphic characters in the execution character set are intended to produce actions on display devices as follows:

…

n (new line) Moves the active position to the initial position of the next line.

r (carriage return) Moves the active position to the initial position of the current line.

so n represents the appropriate char in that character encoding… in ASCII is the LF char

I don't have an old Mac compiler to check if they follow this, but the numeric value of 'n' should be the same as the ASCII new line character (given that those compilers used ASCII compatible encoding as the execution encoding, which I believe they did). 'r' should have the same numeric value as the ASCII carriage return.

The library or OS functions that handle writing text mode files is responsible for converting the numeric value of 'n' to whatever the OS uses to terminate lines. The numeric values of these characters at runtime are determined entirely by the execution character set.

Thus, since we're still ASCII compatible execution encodings the numeric values should be the same as with classic Mac compilers.

C++ For Mac Download

On older Mac compilers, the roles of r and n where reversed: We had ‘n' 13 and ‘r' 10, while today ‘n' 10 and ‘r' 13. Great fun during the transition phase. Write a ‘n' to a file with an old compiler, read the file with a new compiler, and get a ‘r' (of course, both times you actually had a number 13).